Joumou! Joumou!

It’s always time to think about cooking up a big pot of Soup Joumou for the New Year–or whenever the sky is grey and cold breezes blow, and we have a couple of hours to devote to soup-making! Thanks to two friends, Jacques and Kate, who brought back genuine joumou seeds from Haiti, these squash vines have commandeered our front and side yards this summer. Now, Chef Geraud is gently tucking the fruits under boxes on cold nights, and anticipating the day he can use real Haitian joumou squash in his soup joumou.

Haitian joumou is a Haiti-adapted Cucurbita (C. maxima or C. moschata) that is named for and possibly adapted from the French giraumon squash, looks like a small striped green watermelon on the outside, and inside looks and tastes like a pumpkin squash or butternut squash, to which it is closely related. Normally, Haitians in the U.S. or Canada use pumpkin squash or butternut squash for soup joumou. Here in Detroit, we can sporadically find a dried-out hunk of joumou for sale in one of the local Mexican markets, but both availability and quality are erratic. And, as they say, there’s nothing like the real thing!

And what’s so special about authentic Haitian joumou?

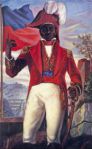

As the story goes, enslaved Haitians were not allowed to eat soup joumou under French colonial rule. Evidently the squash was too rich and aromatic, or too scarce, or simply too, well, French, to be considered appropriate food for enslaved African Haitians. Ironically, of course, squashes are native to the Americas, perhaps as old as 12,000 years, and were taken to France by early returning invaders of the Americas, then returned back to St. Domingue with the French invaders of that island. During slavery, the French told the enslaved Africans that joumou was not meant for Black people—that God had given it to the French, so God would punish the enslaved Blacks if they ate it. But the slaves knew that God did not want them to be slaves, so they mounted a rebellion in 1791 that became their 13-year-long war of independence–after which Haiti became the second independent nation in the Americas (after the United States), and the world’s first Black republic.

According to Chef Geraud, In 1804, the first year of independence, Haitian leader General Jean Jacques Dessalines said that what the French had told the Haitians was a lie—“Eat all the joumou you want,” he said (in Kreyol, of course), “Take a shower in it!” Haitians say when Dessalines read out the Haitian Declaration of Independence on January 1 in Gonaives, that everyone shared soup joumou from public kettles, as cannon boomed and bells pealed. So, now, Haitians thank God every Independence Day, January 1, by cooking, eating, and sharing soup joumou.

In Haiti, joumou can grow in warmth until a December harvest; here, we are hoping it can conquer our cool days and cold nights through all of October. We are crossing our fingers for an edible crop. But, in any case, our Detroit-hardened plants should yield plenty of naturally selected seeds for next year’s crop.

The thick vines and large, white-mottled leaves have long ago conquered our front and side yards, climbing hungrily up and around the lilac and spruce trees, rewarding us as well as curious, smiling neighbors and passers-by with intense yellow blossoms every sunny day. Were we living in Oak Park, surely we would have aroused the wrath of the City Officials with our vegetable-covered lawn! Chef Geraud dismisses the idea of using the blossoms as food–clearly a Mexican and European concept not a part of his family’s Haitian heritage. But, both he and our Cameroonian friend agree that the fresh runner tips make a delicious green vegetable.

Soup Joumou

- 1 lb beef stew meat, oxtail, or goat, with bones, cleaned well in limes and hot water*, cut into bite-sized pieces

- water and 2 cubes chicken bouillon (Maggi cubes)**

- 1 and 1/2 lbs joumou, peeled & diced (can substitute butternut, pumpkin, or kabocha)

- 2 small turnip, 2 small white potatoes, 1 malanga, 1 militon (chayote), and 3-4 carrots, cut into bite-sized pieces

- 1 large onion, chopped

- 1 small cabbage or ½ large, cut into bite-sized pieces

- 1 sprig parsley, 3-4 scallions, & 2 sprigs thyme

- 4 garlic cloves, crushed

- 1-2 cups cressant (watercress) or spinach

- ¼ to one habanero pepper, without seeds, finely minced

- 1/2 cup evaporated milk

- 1/4 teaspoon ground cloves

- 2 tablespoons butter

- 3/4 cup vermicelli, snapped into 2”-3” pieces & 1/2 cup penne, ziti, or rigatoni (or other pasta)

- salt and pepper to taste

In large pot, cover beef generously with water and bouillon, bring to a boil and simmer about an hour, until tender. Bring 3-4 cups of the water to a boil; add squash, roots, cabbage, onions, parsley, thyme, scallions, and garlic. Simmer until squash is tender (15-20 minutes). Roughly mash squash. Add milk, cloves, butter, and pasta. Cook until pasta is al dente. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Serve hot with rice or bread and avocado.

In large pot, cover beef generously with water and bouillon, bring to a boil and simmer about an hour, until tender. Bring 3-4 cups of the water to a boil; add squash, roots, cabbage, onions, parsley, thyme, scallions, and garlic. Simmer until squash is tender (15-20 minutes). Roughly mash squash. Add milk, cloves, butter, and pasta. Cook until pasta is al dente. Season with salt and pepper to taste. Serve hot with rice or bread and avocado.

* Probably because of the tropical heat spoilage risk, Haitians clean all meat thoroughly before cooking, using limes and hot water. When Chef Geraud and his friends came to the USA from Haiti, they were appalled that we often cook meats without washing them thoroughly first, or drop meat directly into a fryer, then eat it still red at the bone.

** Maggi cubes, thyme, clove, and garlic constitute the “holy quartet” of Haitian seasonings. Many recipes also include tomato paste, habanero peppers, and onions.

Pondering Pronouns . . . and Prepositions

Pennebaker, James W. 2011. The secret life of pronouns: What our words say about us. New York: Bloomsbury Press. 290 pages, plus a 9-page “Handy Guide for Spotting and Interpreting Function Words in the Wild,” as well as endnotes, bibliography, and index.

________________________________________________________________

I was eager to read what Prof. Pennebaker had to say about pronouns because, over more than 30 years of teaching college-level courses in humanities, anthropology and English composition, I have become fascinated with the diverse ways students use prepositions in writing.

Now, pronouns are not, of course, prepositions. But, like prepositions, they are “function words,” short, generally two-to-five-letters, and we rarely think about them as we speak or write. Nouns, verbs, even adjectives and adverbs: these we consider carefully (or should) when we use them. Do I refer to someone I work with as an office partner? Colleague? Co-worker? Was the choir singing or chanting? Do I check my email often? Frequently? Daily? Regularly? Hourly?

We may pause in our speech or writing to consider these choices. Rarely, however, do we even think that there might be a reason to consider pronouns or prepositions. They flow automatically, unconsciously.

Nonetheless, my students, many of them, use prepositions differently than I do. I write “about” landscapes, while my students write “of” or “on” landscapes. I go “to” a friend’s house, while they go “by” a friend’s house. They walk “in” a classroom, while I walk “into” a classroom. I regularly encounter usages like these:

“This is all the governments fault in how we eat.”

“This component within itself is not healthy.”

“For my experience watching TV shows, many of them are violent.”

“These fall hand and hand.”

“The plants were grown on bad soil.”

“We want to prevent those animals for feeling pain.”

“How you eat is just as important to what you eat.”

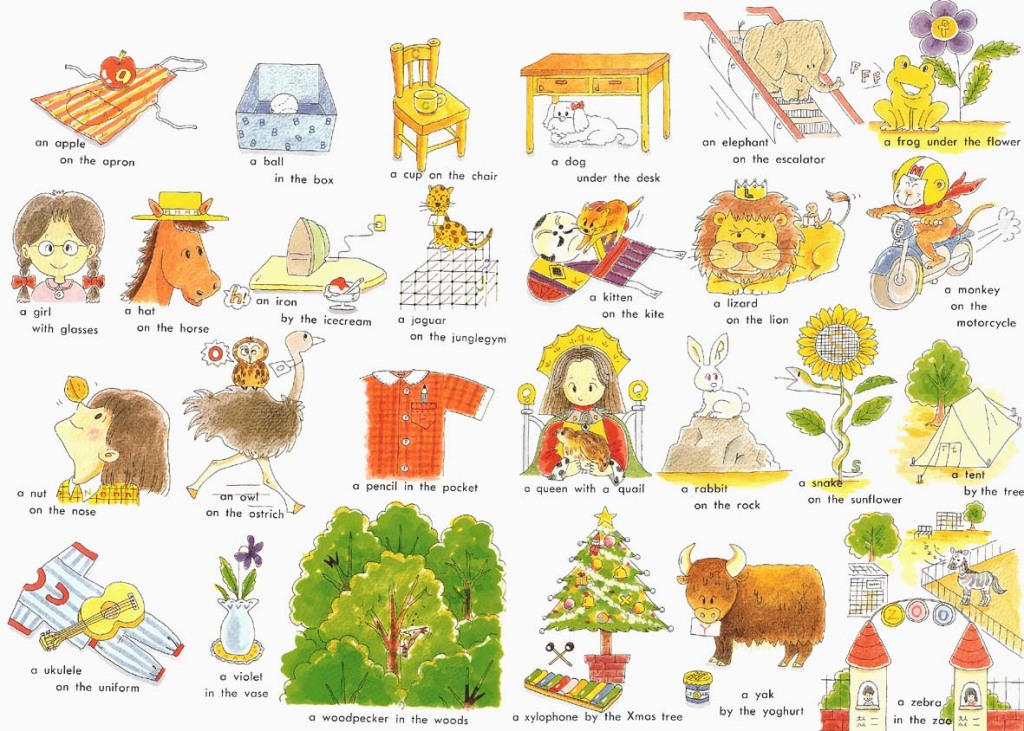

Despite my fascination with these non-standard preposition usages, however, I have never thoroughly investigated them. I have, however, distributed lists of our 100+ English prepositions. In one class, I even devised an exercise for students to act out “on the table,” “at the back,” “into the room,” “around the table,” “in the doorway,” “over the desk,” and a few more of those 100+ prepositions.

Meanwhile, over the past 20 years, using a computer program he developed (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count, LIWC), Pennebaker has analyzed texts upside down and inside out (letters, novels, emails, and essays) to assess psycho-social differences in the use of pronouns and other words (e.g., articles, emotion descriptors, subjective tense, and multi-syllabic words. Statistically, Pennebaker has found that these (subconscious) word choices can signal differences in hierarchical status, gender, relationship status, honesty, emotion, and geographic regions.

Now, Pennebaker would be the first to agree that these differences are statistical, not absolute. So we can’t necessarily rely on pronoun analysis of a friend’s emails to assess her psychological state. But his work does grant us great insight into yet another way we send socio-psychological signals to each other. As well as signaling our statuses with our dress, posture and gestures, handwriting, and speech pronunciation, we really might want to watch our Ps and Qs—at least the Pronouns!

In the great tradition of scientists who are not reluctant to use themselves as experimental subjects (cf. Altman 1998), Dr. Pennebaker offers up some of his own emails (p. 179), asking us to note that people of lower status tend to use more I-words, and those of higher status use more you- and we-words. First, his correspondence with one of his students:

Dear Dr. Pennebaker:

I was part of your Introductory Psychology class last semester. I have enjoyed your lectures and I’ve learned so much. I received an email from you about doing some research with you. Would there be a time for me to come by to talk about this?

Dear Pam:

This would be great. This week isn’t good because of a trip. How about next Tuesday between 9 and 10:30? It will be good to see you.

But note the shift when Pennebaker corresponds with a professor of greater status and fame:

Dear [Famous Professor]:

The reason I’m writing is that I’m helping to put together a conference on [topic] . . . I have been contacting a large group of people and many have specifically asked if you were attending. I would absolutely love it if you could come . . . The only downside is that we can’t pay for any expenses . . . I think the better way to think about this gathering is as a reunion rather than a conference . . . I really hope you can make it.

Dear Jamie:

Good to hear from you. Congratulations on the conference. The idea of a reunion is a nice one . . . and the conference idea will provide us with a semi-formal way of catching up with one another’s current research . . . Isn’t there any way to get the university to dig up a few thousand dollars to defray travel expenses for the conference?

Of course, the most fascinating applications of Pennebaker’s computer-aided analyses are to discover the true identity of anonymous writers, and to separate out liars from truth-tellers. And, can pronoun analysis help with these questions? Yes, it can. Is it 100% fail-proof? No.

And, for the rest of the story, you’ll have to read the book. But you will find it, I assure you, an enjoyable experience!

The Happiest Man

Borgenicht, Louis. (1942). The Happiest Man: The Life of Louis Borgenicht, as told to Harold Friedman. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

***********************************

This book has been intriguing me since I first began reading it . . . so let me tell you about it.

In late January this year, two weeks into teaching an online Cultural Geography class, I read a New York Times article entitled “Historic Dirt Preserved,” (Martin 2012), noting that a 740-acre New Jersey farm was being sold to two different buyers, a doctor creating a vegan agritourism farm, and a British investor planning cider-apple orchards.

The property, a historical landmark, had been sold to New Jersey’s Agricultural Development Board by “New York garment business millionaire Jack Bordenicht [sic]” and then by the Board to the State of New Jersey, with the proviso that it never be used for non-farm development.

The property, a historical landmark, had been sold to New Jersey’s Agricultural Development Board by “New York garment business millionaire Jack Bordenicht [sic]” and then by the Board to the State of New Jersey, with the proviso that it never be used for non-farm development.

I was curious about the connection of this farming land to a Manhattan garment district millionaire. Some remembered Jack Borgenicht as an eccentric nudist, a “greedy” self-centered capitalist and real-estate developer, and resented that he left his wealth to Virginia research institutes, rather than to the states of New York and New Jersey, where he accumulated his wealth.

An article in NJ.com, an online source for New Jersey local news, called him “an eccentric millionaire . . . who amassed three Rolls-Royces, four wives, 10 children, thousands of acres, and a garment-industry fortune” (Goldberg 2010).

Jack, the youngest of Louis and Regina Borgenicht’s 14 children, says that he took over management of his father’s garment business during the Great Depression at age 19, disparaging two older brothers who preceded him as “untalented idiots.” He also referred to a sister as an “ugly duckling” and to her husband as “another idiot.” Jack saw himself as the savior of the failing family business. “It took me six months,” he said, “to turn it around” (Freehling 1996).

Jack’s father Louis was one of many immigrant Jewish entrepreneurs who built Manhattan’s famed garment industry during the 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1888, 234 of New York City’s 241 clothing factories were owned by Jews with production worth $55 million annually. By 1900, the industry grossed over $100 million a year, and employed 45,000 people. By 1913, there were over 16,000 factories (most with 10 or fewer sewing machines and workers) and over 300,000 employees. One estimate is that 85% of garment industry workers were Jewish immigrants from Germany and eastern Europe. The repetitive cutting and sewing did not require skills, education, or a new language (Jewish Virtual Library 2012).

While some factories provided familiar meals, language, and family-like homeland ties for young immigrants, as well as economic opportunities, others became the infamous squalid sweatshops that reformer Jacob Riis described in his renowned photojournalist study, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York (1890).

I was excited to see that Louis Borgenicht had written his memoir, published in 1942, the year he died, titled The Happiest Man.

This I had to read!

How could a man who must have amassed a fortune from the misery of thousands of sweatshop laborers consider himself “happy”?

His memoir revealed several surprises. For one, Louis barely mentions his youngest son Jack, and never by name. Far from crediting Jack with saving the family business, Louis credits God, his wife, five friends who extended credit, and Roosevelt’s National Recovery Act of 1932.

Most astounding, I discovered that Louis, far from appearing as a greedy capitalist benefiting from the neglect and purposeful impoverishment of his laborers, was himself a hard-working laborer.

He began his own life as an often-hungry boy in the village of Zakliczyn, in Polish Galicia, growing up in persistent poverty. “There,” he says, “I lived the life of a peasant. I wore the same tattered clothes. I had only a shirt, trousers and boots.The shirt I slept in, winding myself in its long tails for a little added warmth. The boots I reserved for Sabbaths and holidays.”

During the summers, everyone worked in the potato fields, “kneeling for hours on end and hunching along the furrows from plant to plant. The work began at daylight and ended after sunset.” For lunches, they had two slices of black bread and cool water from the nearby spring. For a time, he and his brother Moische collected the abandoned bones of dead animals, dried them in their yard, and then ground up and sold them as fertilizer.

Louis had a strict Jewish education in the 1860s–paid for in chickens! Louis envied the fine long black coats (bekishe) worn by Jewish men, and saved his pennies to buy one. When his father’s brewery failed, he took one apprenticeship after another, working from sunup until late at night, paid only in room and board. Over the years, he moved from town to town, and from Galicia to Hungary, building his knowledge and skills in the cloth trade. Finally, in 1888, he moved with his new young wife to New York.

To pay rent on their tiny tenement room, Louis tramped all day through cold streets, by turns selling herrings, then towels, tablecloths, notebooks, bananas, socks, and dishes.

Finally, he and his wife began cutting and stitching girls’ aprons by hand, working fifteen hours a day, and slowly building up a business in manufacturing clothing, primarily girls’ and women’s dresses. “Since those aprons had to be turned out as quickly as possible,” he tells us, “there were no union hours for us. We worked late into the night, and stopped only when we could no longer see the cloth in front of us.”

Louis prided himself on his strict honesty and concern for his workers, paying them three or four times the usual rate. “I paid ten and twelve dollars a week,” he says. “In those days we paid by the week, so that there was no speed-up like that of piecework, where the worker is paid by the amount he turns in.”

Louis tells us that other employers, “taking advantage of the constant flood of immigrants and the resultant unorganized, cheap labor, took in learners, at two and three dollars a week. They kept them as ‘learners’ long after they had grown skilled. I found, on the other hand, that able girls, decently paid according to the level of the times, gave better work and friendlier work.”

He and his wife often shared dinner with their workers, and included them on weekend outings with their own children. Even years later, Louis tells us, when they lived in a large house, he often came home to find that house brimming with needy strangers whom Regina had invited to eat or sleep.

By 1892, he and Regina employed 20 young women, making and selling dresses from their retail shop. He maintained an unstinting love, care, and labor for his ever-growing family and the Jewish community. By 1913, he had built a huge wholesale business, and truly became “the happiest man.” In 1938, the United Infants’ and Children’s Wear Association honored him for 50 years of “leadership, guidance, and ethical business conduct.

During the great Depression of the 1930s, however, when Louis was in his 70s, he began to see his own business, as well as his hopes for a perfect American society, with opportunity for all, slipping away. It pained him to realize that modern technology in the industry had robbed workers of the opportunity to build their own businesses.

For me, in 2012, it was a joy to read the simple tales of a young man’s daily toils and thoughts, and to glimpse one man’s vision of life in an American city a hundred years ago.

***********************************

Freehling, Alison. (1996, January 1). High Profile: Jack Borgenicht . Hampton Roads, Virginia: Daily Press: http://articles.dailypress.com/1996-01-01/news/9601010056_1_peace-studies-william-and-mary-mount-rainier

Goldberg, Dan. (2010, December 7) N.J. to Purchase, Preserve Millionaire’s Long Valley Land as Open Space. NJ.com: http://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2010/12/nj_to_purchase_preserve_eccent.html

Jewish Virtual Library (2012). New York City. Jewish Virtual Library (from Encyclopedia Judaica, 2008, Gale Research Group): http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0015_0_14806.html

Martin, Antoinette. (2012, January 26). Historic Dirt Preserved. The New York Times Online. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/29/realestate/new-jersey-in-the-region-historic-long-branch-farm-sold.html

Riis, Jacob. (1890). How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the tenements of New York. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

African by Any Other Name? A Note on Origins

Over the past few days, one of my facebook friends has been delving into the study of African textile arts, after years of loving, wearing, and creating the beautiful headwraps used by African and Islamic women throughout the world. Zarinah also teaches women how to create the incredible cloth crowns, a modern Michigan Johnny Appleseed, enthusiastically sowing the seeds of this ever-changing and beautiful women’s art.

Women praise-singers, La Lutte, Dakar, Senegal, 2009

On reading a well-researched article by Julia Felsenthal on Slate, The Curious History of “Tribal” Prints, Zarinah was crushed. What? All those lovely African printed fabrics are not really African? Instead, they are Indonesian! Or are they? Perhaps they are Dutch? Turkish? Anglo-Indian? Chinese? Or all of these, and more?

At the Mayor’s election party, in the suburbs of Dakar, 2009

As Duryodhana says of Kano in the Mahabharata: “Birth is obscure, and men are like rivers, whose origins are often unknown.” It is exactly that multiplex, tangled, snarled, inter-woven and often hidden history that makes these cloths such an apropos metaphor for artist Yinka Shonibare.

How can we, in the United States, speak of origins, we whose Founding Father all but eliminated the original custodians of this land? We whose colonial antecedents tore millions of Africans from their homes, insisting they “forget” their origins? We who often sneer at or attack people desperately seeking to come here to work, without forgetting their families, their homelands, their origins? We who refuse to study “history” and who prize today’s three-letter text message over dusty old books or sitting at an elder’s knee? We who would rather spend $10,000 on Disneyland than on a trip to Morocco, Nigeria,, Japan, Mexico or France? We who refuse to memorize ancient poetry, or learn even one other language? We who have no idea that the very chocolate, tomatoes, corn and potatoes we eat daily were planted, developed, and named by the earliest Americans–Mexicans and Peruvians–thousands of years ago?

Does that history make cornbread, hoe cakes, or spoon bread any less traditional Black Southern food? Are the fresh-roasted ears of corn I buy in the markets of Cotonou are not “African”? Since Coca-Cola has (or used to have) kola nuts in it, does that make it “African”?

Coca-Cola sign, Ile de Goree (Dakar, Senegal), 2009

Selling kola nuts in Dakar, 2009

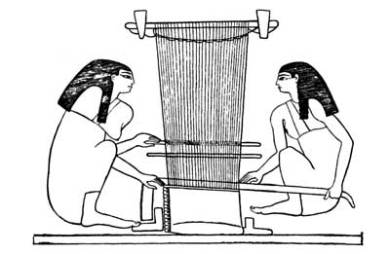

Perhaps even Ghanaian kente cloth is not “African,” since cotton (named from an Arabic word) was first cultivated in India, and now most kente is made of French-invented and European-manufactured rayon). The bright-colored silk in older kente was unraveled from cloth imported from China since about 1500 CE (originally, kente was only cotton white and indigo blue). As for looms, a “loom” can be as simple as a tree-branch to hold tight the warp threads, with the other end tied at a person’s waist (a simple backstrap loom). We have several drawings of both horizontal and vertical looms from ancient Egypt, the earliest, from the tomb of Chnem-Hotep, is dated about 4500 BCE. But we have no idea if either horizontal or vertical looms were invented once (it’s unknown where) or in many places and times.

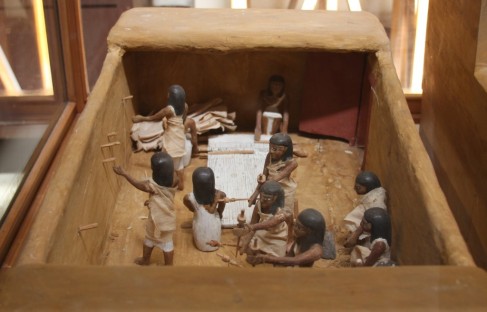

Drawing of Egyptian (KMT) loom from tomb of Chnem-hotep

Model weaving studio, tomb of Meketre, ancient Egypt (KMT), 1975 BCE

So, is cotton African? Are looms African? Are indigo & other natural dyes African? Modern aniline dyes and rayon are manufactured, not “traditional.” But, ironically, the word aniline, coined in 1843 by a German chemist to name the chemical base used to manufacture artificial dyes, is a loan word from Portuguese anil for the indigo-bearing shrub, from the Arabic word an-nil (indigo), from the Persian nili, and ultimately from the Sanskrit nili, indigo, and nilah, dark blue.

Selling hand-dyed indigo cloth in the HLM market, Dakar, Senegal, 2009

So does all this make kente cloth not “African”? Surely this iconic cloth, its manufacture and embedded symbols so entwined with Akan royalty and spirituality, is deeply, essentially African.

All humans are ultimately African, and it is inherently human to travel far distances (IRL or virtually!), to find new things and new people, to learn from each other, to pass on wisdom, knowledge, and skills not only within our own families and communities, but with everyone. In brief, over my lifetime, I have learned not to romanticize “origins,” especially since that quest often implies a search for the aboriginal, unsullied, pure and pristine but also the primitive, archaic, or undeveloped. These are all Eurocentric romanticized concepts. Instead, I am learning to revel in unraveling, at least for a while, the amazing threads people, ideas, and things weave as we re-create ourselves, our ideas, and our societies over and over.

On Death and Dying

Written October 22, 2011

For the past week, I have been teaching a unit on festivals of death: beginning with Hallowe’en, that strange mash-up of the ancient cross-European Celtic Samhain farmers’ new year/harvest festival with odds and ends of other harvest festivals like the Roman Pomona and the perhaps universal practices of small-scale personal divination (fortune-telling), global masking and role-reversal traditions. And, most of all, our intense need to remember, honor, and call on our dead ancestors for

their ongoing advice, protection, and love, without, of course, having them return as ghouls, since they are, as the people of Oz declared of their wicked witch, “ Morally, ethically, spiritually, physically, positively, absolutely, undeniably and reliably dead . . . and she’s not only merely dead, she’s really most sincerely dead. ”

Oh, and, lest we forget the water we swim in—this strange amalgam of global and local Hallowe’en heritage come to us all tied up in a package of opportunistic capitalist marketing of everything scary, or playful, or merely orange and black, from jelly beans to kitchen towels.

This week, the class will explore a few of the world’s many festivals of death: the Mexican Dias de los Muertos, the Haitian Ghede festival, the Nigerian Yoruba Egungun ancestor masquerades, and the northern Michigan Odawa ghost suppers.

*********

Now, amidst this focus on the annual death of our brief summer luxuriance, and the forever deaths of humans, friend and foe, came a death. A death of a man not so very close to me individually or personally, but close to many people who have been close to my husband and me for the past 15 years.

So, yesterday and today, I have been participating in our own received rituals of death: the funeral home rites, church services, graveside prayers, and communal feast—all in honor of a gentle man, an ordinary man, a man like my own dead mother and father, an ordinary man and woman. A man who lived, worked, loved, and died, doing his school lessons and his work, caring for his wife and children, loving his homeland, loving his coffee, his cigarettes, his music, his dancing, his impassioned political discourses, doing the best he could.

*********

I have cried a lot this past week, and I think: I am crying for my own losses. For my father’s joyful intelligence, his self-absorbed internal conversations, our comradely swims and sails, our shared tasks and disputations, walks up and down hills, into woods and quarries, through cemeteries. For my mother’s shrewd, sharp sarcasm, barely suppressed, her quick wit, her wise words, her quiet queenly sedentary ways, our shared coffees and teas and word games, our silently shared uncertainty about life’s truths.

Yes, I know that I am crying, too, for more losses yet to come: the day I bury my brothers, my husband, my friends. And so I talk with my husband about this: don’t bury me—burn my bones into ashes, and scatter them where you will. Or grant my body to a medical school. Or, if you cannot, if you must bury me, bury me in a simple pine box, and give a big party, in a big empty space, so everyone can dance.

In my own internal conversations, I hear Gerald Manley Hopkins’ words repeated over and over throughout these past days, words penned in Lancashire in 1880, 131 years ago, but published in 1918, the year my father was born:

Spring and Fall

to a young child Margaret, are you grieving Over Goldengrove unleaving? Leaves, like the things of man, you With your fresh thoughts care for, can you? Ah! as the heart grows older It will come to such sights colder By and by, nor spare a sigh Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie; And yet you will weep and know why. Now no matter, child, the name: Sorrow’s springs are the same. Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed What heart heard of, ghost guessed: It is the blight man was born for, It is Margaret you mourn for.This afternoon, as we left the post-funereal communal meal, one of my favorite dance partners took my hand, and said, “We must dance.”

This is the wisdom of Haitian men and women.

We dance while we are here.

We dance.

*********

“There is a vitality, a life force, a quickening that is translated through you into action, and because there is only one of you in all time, the expression is unique. If you block it, it will never exist through another medium and will be lost. The world will never have it.” —Martha Graham.Chai by Any Other Name?

Last year sometime (2011), I found I had to go shopping for an inexpensive Chai mix (a.k.a. karha), as my big glass jar from a now-defunct spice shop was sadly depleted. Lo and behold, I discovered that a jar of “Chinese Five Spice” seemed to have just the right mix for making Chai!

I revel in these late-life discoveries, though I always wonder why it took me so long to discover them. And I remember my mother’s joy when, pushing 90, one sunny summer day vacationing in northern Michigan, she finally gave in to my brother’s urgings to sample cappuccino, and found a new minor thrill in life.

So, of course, I bought the jar of Chinese Five Spice, as it was much less expensive than any Chai mixture I’d found, and I took to scooping a teaspoonful of the mix into a pot of black tea for Chai, ready to embellish with honey and milk for a cozy treat.

Then, last month, I ran out of the Five Spice mix, and determined to make my own. Lo and behold again! In searching online for various mix proportions for Chai and for Chinese Five Spice, I discovered that Garam Masala is also basically the same spice blend. Life is sweet, indeed (and spicy).

Of course, everyone has his or her own version of these three amalgams, using different spices (even “five-spice” mixes may have six or seven or eight different spices) as well as different proportions. All of the spices included in these blends have healing properties, e.g., as analgesics, anti-oxidants, anti-inflammatories, and anti-microbials, as does tea (Camellia sinensis), which can lower levels of cholesterol and blood sugar.

I read up on Chai, Chinese Five-Spice, and Garam Masala, cruised a few dozen recipes, and then went shopping at my favorite spice shop (also, admittedly, my favorite shop for olives, nuts, fresh meats, and fresh fruits & veggies), Papaya Market. I needed to stock up on the ground spices I didn’t already have in sufficient supply. I didn’t want to grind my own spices this time, just in case my trusty little Braun grinder, which I use for spices and flax seeds, wasn’t up to all that work at once. I know the spices at Papaya Market are fresh and pungent. The only change I’d like to make next time is adding star anise, which I can’t yet find locally.

Of course, once it was blended, I had to sample it as Chai (a.k.a. Masala Chai), and then package up some of it to share with five friends (if you didn’t get yours yet, just ask!). Here’s the current concoction:

Chai Masala a.k.a. Chinese Five-Spice a.k.a. Garam Masala

Make sure your spices are freshly ground and pungent. Thoroughly mix together these ground spices: 4 T cardamom, 3 T allspice, 3 T anise, 3 T cinnamon, 3 T ginger, 2 T black pepper, 2 T cloves. For Chai tea, mix with strong black tea (about one teaspoon per pot), real vanilla extract, honey (or sugar), and milk to taste. Mmmmmmmmm.

UPDATE: (2024). I still enjoy shopping at Papaya Market, and still grind spices in my 2009 Braun grinder (though the exact small grinder now retails for $70-$125!). My recipe has changed over the years, primarily because I can now easily purchase star anise, which we use liberally in our household–especially for chili and for Haitian labouyi (porridge).

NEW RECIPE: 3 Tablespoons each of ground Ceylon cinnamon, powdered ginger, ground nutmeg, & ground cardamom; 2 Tablespoons each of ground black pepper, ground allspice, ground cloves, and ground star anise. Add about one teaspoon per pot of strong black tea (preferably Assam, Darjeeling, or Ceylon). After steeping, mix as preferred with jaggery, panela, honey, or Demerara sugar, and milk. Some people like to add vanilla essence.

Cake by Any Other Name?

On Banana Bread:

This afternoon, stuck at home without a car, and without anywhere enticing enough to walk to through cold and snow, I decided it was time to turn those black shriveled bananas into banana bread.

As always, I first had to spend some time pondering why we insist on calling tea breads or quick breads “bread,” when they are clearly cakes, leavened with baking soda and/or baking powder instead of yeast, and concocted with prodigious amounts of sugar, honey, or other sweeteners.

To use the term “bread” for the savory variations, such as biscuits, cornbread, dumplings, fritters, beer bread, soda bread, or pancakes, would not seem out of place, as they usually contain little or no sugar—note, however, that we do say “pancake” and not “panbread,” despite the usually low sugar content of pre-syrup pancakes! Unleavened johnny cakes (a.k.a. hoe cakes) also are usually not sweetened. So–why are they cakes?

Using the word “cake” for unsweet floury lumps is not too hard to explain, given the Old Norse word for cake, kaka, seemingly a global word for lumps of shit. So, by analogy, any lump is a cake (as with mud caked on one’s boots).

Surely, though, the sweet “breads” should properly be called cakes? Some sweet yeast-less flour doughs have their own names—scones, brownies, muffins (not to mention pastas). We don’t have to fret over whether they are “cakes” or “breads.” A “cookie” is already a cake–the word comes from the same Germanic (ultimately Indo-European) root word as “cake”—in Dutch, cake and cookie are koek and koekje. But why do we say make cranberry bread and banana bread? Ginger bread and apple bread? Pumpkin bread and zucchini bread?

The most satisfying solution I’ve come up with so far is that “tea breads” are sweet because, in England, both children and adults like sweet cakes (breads?) with their afternoon tea. Thus, breads for tea, whether leavened with yeast or baking soda, are sweetened for afternoon tea.

And then, too, perhaps quick breads were all originally unsweetened breads—a simple soda bread, and the same breads, even when later sweetened, retained their original designation.

In any case, I had nine nice flabby black shriveling bananas, filled with soft, mushy pulp, just waiting to be made into banana bread. And I knew exactly how I wanted to make it, since I’d previously used all whole-wheat flour, less sugar, and more fiber, and ended up with a truly delicious loaf. I also like to use a lot of spices in cooking and baking, especially when there’s the taste of flax seeds to counteract. Feel free to use your own favorite spice mix!

So, here’s the recipe for two loaves, one of which was rapidly and ravenously devoured by friends and family:

Moist Whole-Wheat Banana Bread

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Grease and flour two loaf pans, 8 ½ by 4 ½. Stir together in a large bowl: 2 ½ c whole-wheat flour, 2 t baking soda, 1 t baking powder, 1 t salt, ½ t ground cinnamon, 1 t ground ginger, and ½ t allspice.

In another bowl, beat together well: 1 c unsalted butter at room temperature and 1 c brown sugar (light or dark).

Then beat in well: 2 c mashed ultra-super-ripe bananas, 4 large eggs, and 2 t real vanilla extract.

Stir in well: ½ c freshly ground flax seeds, ½ c rolled oats (not instant), and 1 c chopped walnuts (pecans are also an excellent choice, and raisins would not be unwelcome).

Fold in the flour mixture until just mixed. Divide evenly into the two pans. Bake until the edges begin to pull away from the sides of the pans and a toothpick inserted into the center of the loaf comes out clean, Cool in the pans atop wire racks for ten minutes, then carefully turn out the loaves onto the wire racks and cool, completely. Eat and enjoy! Even better buttered, if you wish.

Joumou Conquers Detroit!

Fittingly perhaps, on a day set aside to commemmorate (if not exactly celebrate) the first landing of Cristobal Colon and his three-ships-full of conquistadores, somewhere in the Bahamas, Chef Geraud has harvested his first Detroit-adapted Haitian joumou squash. And a fine, hale and hefty squash it is, me hearties!

We watched & worried over the joumou all summer, as the running tips reached a few extra feet each day (it seemed), and the sun-bright female blossoms slowly birthed dark green belly-bubbles, and the little dark green bubbles blew up into pale, striped, heavily pregnant orbs.

So today Chef Geraud, midwife to our food, delivered the first of the crop. I wonder about its ancestral migrations, its origins and wanderings. But, as Duryodhana says of Karna in the ancient Indian epic story of India’s birth, the Mahabharata, “Birth is obscure, and men are like rivers, whose origins are often unknown.” And so it is for squashes, as for men.

Varieties of squashes (genus Cucurbita) originated, botanists say, in Mesoamerica, where they were first cultivated 8,000 to 10,000 years ago, where they wound their tendrils greedily up corn stalks and into the hearts and bellies of the first American people, who honor them as one of the Three Sisters of cuisine: maize, beans, and squash.

I imagine these hardy edible seeds, prized also as medicine, tossed out everywhere the squashes were cut open to be cooked fresh or dried, or carried as a snack, like we do now, trail food for long hikes and water voyages, wending their adaptable way throughout Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean, then north into North America, to the Odawa and Potawatomi and Ojibwe people of Michigan, borne by people, or birds, or like Karna, borne by the waters to their new home.

And so the Chef and I are re-telling an old story, as old as Karna, the warrior abandoned as a baby in a basket among the reeds, as old as the Mahabharata story of the battle for the Ganges River valley. As old as the chinampas of Mexico, and older. We are handmaidens to the Squash Story, wet-nurses to the Second Sister, helping her spread her restless tendrils into our Zone 6 front yard in Detroit. No matter our status is lowly; we are well rewarded. Bring on the Soup Joumou!

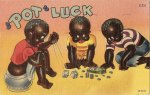

Hateful Things: Racist Postcards c. 1900-1960s

In 2005 and 2006, as I was intensively updating my research on West African textile arts, assisted by a brief sabbatical leave from Marygrove College, I found that, depending on the online search terms I used, I would encounter information and images related to cotton manufacture in the U.S. southern states. At times, these images were either subtly or overtly racist; many of the images were imprinted on postal cards.

I decided to undertake this tangential search for further racist postcard images, and discovered a veritable cornucopia of 4 x 6 demeaning stereotypes, hatred, terrorism, and even pedophilia and death-wishes. These cards were created and sent primarily during the “Jim Crow” period of U.S. history, from around 1900-1910, when postcards became wildly popular, until the mid-1960s, when the Civil Rights Act sent the most overtly racist forms of popular culture underground.

As difficult as it was (and is) to confront so many hateful images, studying their recurrent themes helped me to answer a question I’ve wanted to answer since my youth: how were (and are) so many white Americans convinced of the truth of racist propaganda, even when they themselves benefit little or not at all from the social economy that propaganda supports?

Not wishing to reward people selling these cards, either reproductions or the original versions, I downloaded a few dozen digital images into a PowerPoint slide show presentation for purely educational purposes, used to instruct students in Humanities, Black Film, and Cultural Geography courses.

Educational collections of actual postcards are maintained by David Pilgrim at the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia (Ferris State University, Big Rapids, Michigan), and by Khalid el-Hakim, a former student of Pilgrim, at his Black History 101 Mobile Museum based in Detroit, Michigan.

A brilliant 1987 documentary by Marlon Riggs, Ethnic Notions, positions such postcards within a wider culture of popular daily and household objects supporting white supremacy (e.g., cookie jars, ashtrays, sheet music, children’s songs and games, political cartoons, animated children’s cartoons, and Hollywood films). A 5-minute clip from Ethnic Notions is available at California Newsreel, which sells the dvd, and the complete text transcript is also available online. Unfortunately, we lost Marlon Riggs to AIDS in 1994; Ethnic Notions as well as his other documentaries, Color Adjustment and Black Is–Black Ain’t are his still vibrant legacy.

Those seeking to understand the use of popular culture to advance white supremacy may also benefit from the 1997 bell hooks documentary, Cultural Criticism and Transformation, available at amazon.com and on YouTube.

Here is the link to my PowerPoint slide show, last updated in April, 2011.